Friday

Leaving Inverness, Scotland before 8 a.m. Friday, August 8, 2006, Yvonne and I said goodbye to our friends and drove north to catch the car ferry to Orkney. Barb and Dean were off to St. Andrews on a golf pilgrimage and Tessa and Alan were going south to England to visit Tessa’s cousins. Ann and Dave, via a different route, would meet us on Mainland, the largest and most heavily populated of the 70 islands that make up Orkney.

Because of its stone circles, tombs, and village sites, Orkney was a natural extension of our neolithic focus in Scotland. But it was something more. We lived on an island (Orcas) in an archipelago (San Juan Islands) and we wanted to see what contemporary life was like in another island community.

Three car ferries connect Scotland to Orkney: Aberdeen to Kirkwall; Scrabster to Stromness, and Gills Bay to St Margaret’s Hope, called The Short Sea Crossing (an hour) and the one we chose.

Northern Scotland is covered with heather and few trees and most of those mono-cropped in plantations. It’s beautiful and remote, rolling hills, even mountains, with uninterrupted views in all directions. There are few people, a scattering of small villages, and little traffic on the few roads roads. To us, people from the Pacific Northwest where tall evergreen trees grow like weeds and everything green is happy, the space was forlorn, even desolate. We made good time.

Because we had plenty of time, we stopped near John o’Groats, at Duncansby Head, high on a cliff above the sea where we could look across the Pentland Firth at Orkney. The Duncansby Head Lighthouse at the site was built by David Alan Stevenson in 1924.

The Caithness headlands rise almost vertically out of the water, hundreds of seabirds flying along the red, tan, and moss-covered green cliffs, caves, beaches, and two sharply pointed sea stacks sit off-shore waiting to impale something huge, a dirigible perhaps. Dolphins and seals abound.

The wet wind chilled, we retreated to the warm car, and drove further west to Gills and downhill to its harbor. It was too early to drive aboard the ferry so we sat in the car alternately reading and talking and running the engine to pump some heat into the car.

We had parked among a handful of other vehicles on a large concrete pad, the site of an ongoing construction project by Andrew Banks, owner of the Pentland Ferries. In 1989 the Orkney Island Council had tried to introduce ferry service from Gills Bay and failed. Banks picked up the effort and we were the beneficiaries of his work.

Looking at this ferry landing and comparing it with our experience getting to and from Orcas Island via the Washington State Ferry System, we were newly grateful. Washington considers its ferries a form of public road and so do its residents, willing to subsidize a quality system that wouldn’t work as a for-profit enterprise. We’ve used the British Columbia Ferry System as well. It is more ambitious and truly luxurious compared to Washington’s. When we used the Alaskan ferry system, 2016, ten years later, we were again reminded about the quality of U.S. state ferries.

The contrasts with Washington State Ferry System became more apparent when we drove aboard MV Pentalina-B through its raised bow, parked, and then toured the vessel. The passenger area was cramped with poor ventilation and a greasy cafeteria. Outside there was little room on deck and poor visibility forward, just where we wanted to look.

Pentland Ferries latest ferry for the route, M.V. Alfred, a catamaran built in Vietnam, made its first trip between St Margaret’s Hope and Gills Bay November 1, 2019. Alfred’s flat and wide body can carry almost 100 cars and more than 400 passengers. It joins the 2009 Pentalina, another big catamaran on the Gills/Hope route. We would have enjoyed a ride on either deluxe ferry but we were years early.

The hour-long voyage to St Margaret’s Hope took us into Scapa Flow, an outstanding natural harbor in the middle of the Orkney Islands that Vikings used a millennium ago and that served to protect the British Fleet during the First World War and the site of the German fleet’s eventual scuttling after its surrender.

There are almost no trees on the islands so on approaching they look barren and human constructions stand out on a green expanse. Later, as we we drove around Mainland its agricultural richness became evident. Cow and sheep abound and farms are well-kept and modestly prosperous.

We drove to Kirkwell, Orkney’s largest town, housing a bit fewer than half the islands 22,000 residents. Kirkwell is attractive; a nice place to be. We’d return later in our visit but now we wanted to get to our guesthouse on Old Finstown Road, about seven miles west of Kirkwall.

Avril Osborne, retired from Scottish Social Services on Orkney and our hostess, told us that summer here ends mid-August. Ah! But no surprise. Orkney lies 59 degrees north, almost the same as Oslo and Stockholm. Orcas Island, in comparison, lies just above 48 degrees north and Boulder 40 degrees north. Warmed by the Gulf Stream Orkney winters are mild but summer cool. Wind is constant, gales and fog not uncommon, annual rainfall at 41”, a bit more than Seattle. Winter nights are long but on the summer solstice the sun rises at 4:00 a.m. and sets at 10:29 p.m, lots of daylight.

Even in early August the days are long, so after dinner at the Standing Stones Hotel Bar, a few miles west on the Loch of Stenness, a freshwater lake, we drove to Stromness, Orkney’s second largest town with over 2000 residents. The Vikings called it Hamnavoe, or safe harbor. Ann and Dave would arrive here tomorrow, Saturday, in Stromness via the Scrabster ferry.

Stromness was home to George Mackay Brown (1921-1996), an author and poet I knew by name but not his work. Now in Stromness I bought a copy of his 1994 novel, Beside the Ocean of Time, shortlisted for the Booker Prize. It’s a beautiful and deep story about Thorfinn Ragnarson, “Of all the lazy useless boys who ever went to Norday school, the laziest and most useless.” Thorfinn lives in his imagination and that allows the author to show, rather than tell Orkney history, especially its Viking past that Thorfinn is fascinated with. As a poet Brown is economical with words; there’s nothing extra and what’s there is rich and evocative of people and place.

Saturday

Saturday morning we drove west from Finstown to the Brough of Birsay, an uninhabited island off Mainland, facing the Atlantic, accessible by foot for about two hours on either side of low tide, that day about 6:00 p.m. The wind blew, the waves crashed. We’d come back with Ann and Dave later.

Orkney farm fields are often walled with local yellow Stromness flagstones rather than fenced. The attractive rock splits evenly and easily and so is wonderful for construction. Ancient people here quarried massive sandstone slabs they moved and then set upright to create stone circles we’d come to Scotland to see.

St Magus Church and Earl’s House ruins are close to the Brough of Birsay so we parked for a look-see. The story of St Magnus is told in the Orkneyinga Saga, written in Iceland in the 13th Century about the rulers (earls) of the Shetland’s and the Orkney’s between the 9th and 13th centuries. The story begins with Norwegian Harald Fairhair’s conquest of the islands and along the way describes the murder of Magnus Erlendsson in 1117 after joint rule with his cousin Haakon fell apart. Magnus was averse to violence, unappreciated at the time, and an ax to the head during what he expected to be a negotiation did him in. It’s a very complicated story. In any case, miracles attributed to Magnus subsequently began to appear, he was declared a saint, and several churches in the Orkneys followed, the first in 1136. The modest and attractive church at Birsay dates from 1664.

The ruins of the Earl’s Palace lay nearby, mostly stone walls and chimneys. Built by Earl Robert Stewart, illegitimate son of Scottish king James V, beginning in 1569. After mistreatment by Cromwell’s forces the house fell into disrepair and was mostly abandoned by 1701. Robert Stewart, a notoriously harsh presence used forced labor to build the palace. His son, Patrick was perhaps worse, and his grandson Robert, after leading a rebellion against James VI, was hanged in Edinburgh in 1615. Nasty.

We headed for the Broch of Gurness, perhaps 2500 years old, an Iron Age fort. The broch is built of laid stone, features a small tower, and many small rooms. It lies right on the water and is an interesting area to explore.

Heading south and then east we passed scores of colorful beached rowboats on Loch of Harray. That must mean that fishing is good in this freshwater lake. To the southeast we could see the Ring of Brodgar on a narrow stretch of land between Loch of Harray and brackish Loch of Stenness. At the ring we could understand the choice of setting; water on either side backed by grassy green hills. A beautiful location – for rituals, gatherings, whatever happened here.

The Ring of Brodgar is large, 341’ feet across, and once contained 60 stones though today only 27 remain. And it is a henge, having a flat central area surrounded by a substantial ditch. Brodgar ranks with Stonehenge and Avebury in southwestern England in ambition but it’s more elegant, more accessible, and prettier than either.

Here, in August, the heather was in bloom covering the banks of the henge in purple. Besides ever-present grass, Queen Anne’s lace and other native vegetation added color and texture. We weren’t alone; perhaps another 20 tourists wandered around the circle and between the stones. The wind had abated a bit, the rain held off, but it was cold.

The Ring of Brognar is old, dating perhaps to 2500 BCE, but not the oldest stone circle on Orkney. The Stones of Stenness, arranged in an oval and smaller, about a mile away, may be five centuries or older than The Ring of Brognar.

The Standing Stones of Stenness once numbered twelve but only four remain in the oval. Originally the site had a henge but it has disappeared. Remains of a settlement are nearby.

Maeshowe, a Neolithic passage grave and chambered cairn rises out of a field northwest of the Stones of Stenness and were built later. Our guide explained that on the winter solstice the rear wall is illuminated by direct sunlight through the entrance passage, as happens at New Grange in Ireland, a larger but less sophisticated structure we saw in 2001. It’s not clear Maeshowe was ever used as a grave and some archeologists have suggested it served as an astronomical observation site. It’s also been suggested that Skara Brae, a neolithic village site we saw the next day was connected to Maeshowe by some kind of road.

Inside Maeshowe, our guide explained that Vikings in the Twelfth Century looted the site. Using his flashlight as a pointer he then showed us many of the runic inscriptions the bragging Viking vandals left. The Orkneyinga Saga, cited above relating to St Magnus, names the Maeshowe culprits: Orkney’s Earl Harald Maddadarson and Møre’s Earl Ragnvald.

We’d made arrangements with our friends Ann and Dave to meet at the Brough of Birsay about 5:00 and there they were. A concrete causeway leads to the island, invisible on our previous visit because submerged by the tide. The 7th Century aristocratic Pictish settlement was eventually replaced by Norse settlers in the 9th. The Orkneyinga Saga places Jarl Thorfinn the Mighty (1014–1065) in the the main residence on the small island, center of power on Orkney until it decamped to Kirkwell in the 12th Century.

After touring the ruins and chatting with the warden, we walked uphill and west to the crest of the island overlooking the point where the Atlantic meets the North Sea. An unmanned Stevenson Family lighthouse, built in 1925, continues to warn ships away. Below the sea is impatient and insistent, crashing against the western cliffs of the island as it has time out of mind. It’s a beautiful and dramatic place.

We led Ann and Dave back to Finstown to show them where we were staying and then to Kirkwell where they were guests at the Westend Hotel. We had dinner at their hotel and a long and stimulating conversation touching on themes our group came back to repeatedly during our visit to Scotland (and now Orkney): what’s the right balance between the individual and group; aesthetic and practical; sacred and profane?

On Orkney 5000 years ago when megalithic constructions required enormous communal effort, was there a sense of the individual at all, at least the way we understand it today? Ann is a student of rock art and is fascinated with the interface between the natural world and human artistic and sacred expression. We saw that interface expressed farther south in Scotland but here on Orkney it thrived. The landscape, materials, sea, climate, and culture created what was surely sacred art or art of the sacred.

Perhaps a year later Ann sent me a newspaper article about the Kirkwell Ba Games, held Christmas Day and New Years Day pitting the Uppies (Up-the-Gates) against the Doonies (Doon-the-Gates). A form of mass football, the game has been played on Orkney and around Scotland for more than 200 years and its roots may lie in folklore described in the tale of Sigurd and the Orkneyinga saga. In the Icelandic Poetic Edda, Sigurd kills a dragon and steals its treasure, leading eventually to his own destruction. In any case, the Doonies strive to move the ball “doon” to Kirkwell Harbor and the sea, and the Uppies must round the Land opposite the Catholic Church. The scrum may contain 350 men pushing in one direction or another. I don’t pretend to have any understanding of the event but I suspect it would be exciting to watch though perhaps impossible actually see what was going on.

Kirkwell Harbor faces north, toward the Shetland Islands and its main town Lenwick, 157 miles away. The Shetlands also belong to Scotland but it wasn’t always so. In 875 Norwegian King Harald Fairhair annexed Shetland and Orkney and they were Norwegian until 1468, almost 600 years later, until they were pledged as collateral and then forfeited to James III of Scotland when Christian I of Norway failed to pay his daughter Margaret’s dowry to James.

What’s amazing to me is that the Shetlands were settled at least 6000 years ago and contain over 5000 archeological sites. They’re 228 miles from Bergen, Norway and 157 miles from the Orkneys and northern Scotland. Somehow ancient peoples had what amounted to a maritime highway between Norway and Scotland. The Vikings were following an ocean route that was already ancient when they pointed their longboats south. What kind of vessels did the ancient sailors have? How did they navigate?

Sunday

Overnight the wind came up and the ceiling came down; white mist and blowing rain. Orkney at its best.

We met our friends at The Ring of Brognar, in our opinion the most important thing to see. We didn’t mind showing them around now that we were veterans of the site. I’d brought some dowsing rods from home with the intension of using them to detect something, whatever, at the stone circles we visited in Scotland but hadn’t taken them out until today. We’d see if we could find Ley lines in the Ring. Surely it had been built on an energy line. That’s what made the spot sacred; it was something the neolithic people could feel.

Well, maybe. Yvonne and I had been taught to dowse near Glastonbury in Somerset in the summer of 1984 at the foot of an oak tree processional that pointed at Stone Henge. Only two of the trees were left, Gog and Magog and they were well over a thousand years old. Our guide showed us how to hold a copper rod bent into a right angle in each hand and walk slowly letting them show us where the energy line ran. We found we could do it and later practiced in Boulder and found crossing Ley lines on Flagstaff Mountain. Well, that’s what we told ourselves.

But I had no success whatsoever. The near gale blew the dowsing rods held loosely in my hands every which way. It would not be possible to allow the subtle forces my body felt to be amplified by the dowsing rods I held in my hands. Oh well.

Cold and wet we drove west to Skara Brae.

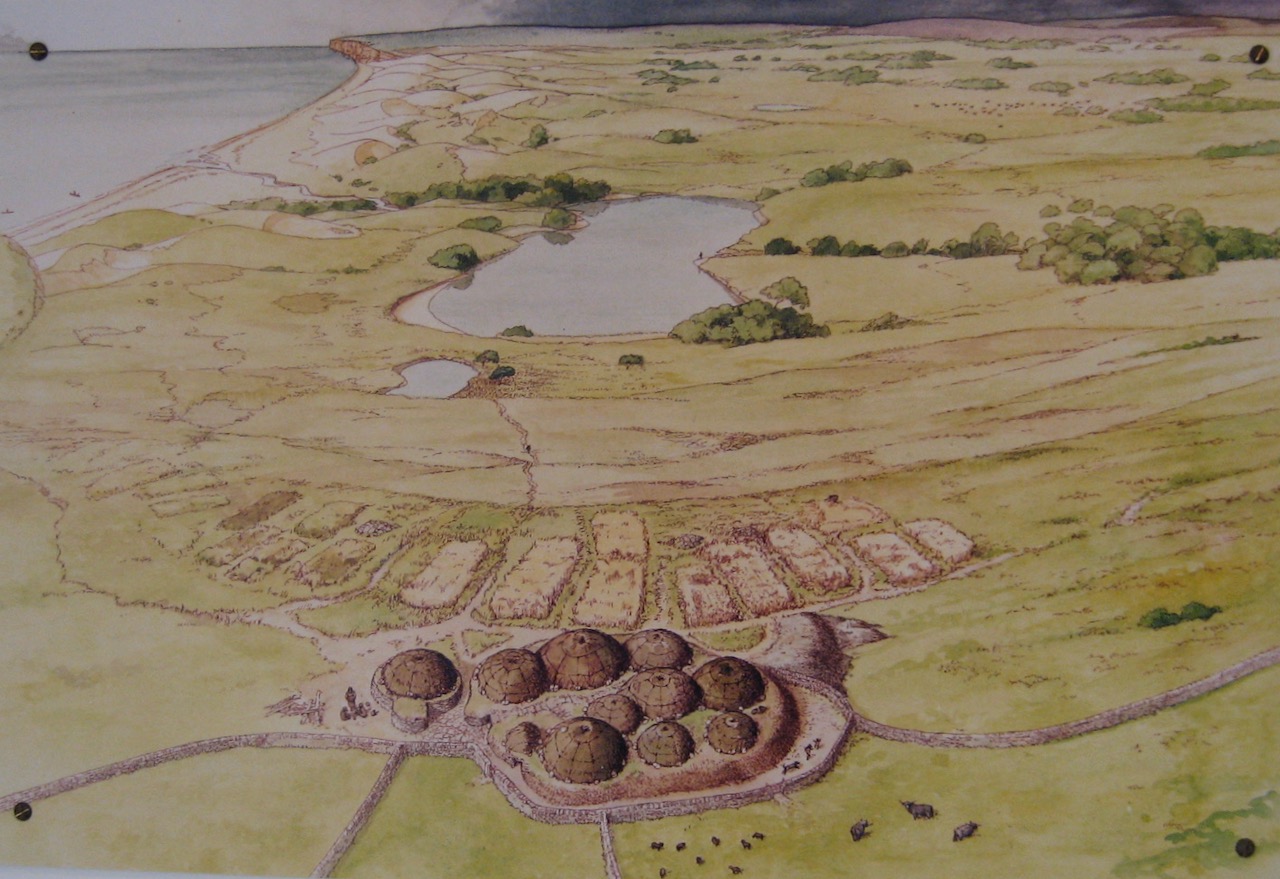

Skara Brae, on the west coast of Orkney Mainland, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, as are Maeshowe, The Ring of Brodgar, and the Standing Stones of Stenness. Built before the construction of the Egyptian Pyramids, Skara Brae lay hidden for thousands of years until partially exhumed by a severe storm in 1850. Radio carbon dating suggests initial occupation about 3180 BC and lasting five centuries until the climate turned colder.

Most ancient residential sites look their age. Millennia of exposure to the elements and humans scavenging can make them unrecognizable as human habitations. But there are exceptions. Pompeii, for instance, is striking because it was quickly buried in ash and pumice in 79 AD by erupting Mt Vesuvius leaving the city intact though unfortunately burying its residents. Skara Brae is a bit like that though without the bodies and millions of tourists.

The eight structures that make up the village were built into a midden (pile of debris) that provided some insulation. Stone slab doors made it possible to keep out some of the cold. A typical layout includes beds (perhaps lined with straw and furs), a cooking area and a dresser-like storage area. These furnished apartments look almost new and were likely cosy places to be in winter.

It’s not certain how the structures were roofed or heated. Like today, Orkney didn’t grow trees or provide sources of peat. Logs from elsewhere may have washed up on Orkney’s beaches and seaweed may have been put to use for roofing and fuel.

The visitors center at the site includes a small museum with a facsimile of a Skara Brae house as well as a gift shop. I inquired about native Orkney music and was directed to “Just a Few Tunes,” a CD by local Orkney musicians, Kenny Ritch (accordion) and his son Kenneth (fiddle). It’s wonderful!

Track 1: Three Good Reels

We had a ferry to catch from St Margaret’s Hope back to Gills Bay so we said goodby to Ann and Dave. From Gills Bay we’d stop in Nairn overnight to look at this seaside resort town (it turned out not really) and then back to Edinburgh, for some more sightseeing, and then fly back to Seattle.

Orkneys and San Juans

Both the Orkneys and the San Juans are archipelagos, Orkneys with 70 islands covering more than 425 square miles and the San Juans with 400 islands covering about 174 square miles. Both have mild climates influenced by major ocean currents (Gulf Stream and Japanese Current) though the Orkneys (at 58 degrees north compared with the San Juans at 48 degrees north) have more rain, wind, and cooler temperatures.

The Orkneys are relatively flat with almost no trees. The San Juans are hilly to mountainous and mostly covered with evergreen forest. The Orkneys have a population of about 22,000 and the San Juans about 18,000.

The Orkneys show evidence of human occupation for at least 6,000 years. The San Juans show evidence of hunting and gathering between 6,000 and 8,000 years ago and villages 2,500 years ago, but weren’t settled by Europeans until 1850. The Orkneys were part of a marine culture that traveled long distances thousands of years ago. The San Juans were also part of a marine culture with long distance canoe travel, fishing, and whaling up and down the west coast of North America.

On Orkney people built with stone, the only building material they had and it persisted. On the San Juans and mainland, people built with wood, especially cedar, into longhouses that had to be replaced from time to time. The people of the San Juans, mostly the Lummi, enjoyed a surfeit of fish, seafood, game, and vegetables of various kinds. It’s unlikely the residents of the Orkneys had it so good.

People of the Orkneys call themselves Orcadians, perhaps in the tradition of the Roman Historian Tacitus calling them Orcades. Orcas Island, the largest of the San Juans, was named after the Viceroy of Mexico, sponsor of the 1791 voyage that “discovered” the island. Orcas residents don’t usually call themselves Orcadians but justifiably could. People on both archipelagos have strong local identities and see themselves as a bit different from people living on the less interesting mainland nearby.

© 2019 – 2020, johnashenhurst. All rights reserved.